I worked at a location that was running a single, world-wide instance of SAP. The whole of their HR, Finance, and some of their manufacturing was running from this single instance, twenty four hours per day, seven days per week.

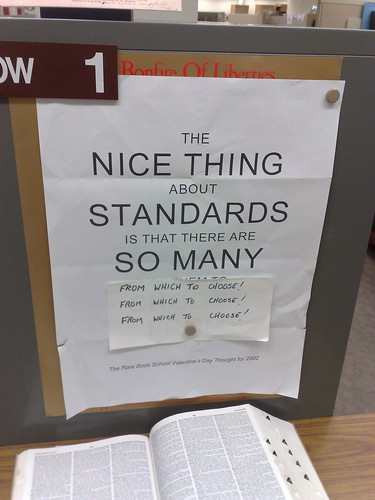

Naturally, the process analyst in me (and to some extent, the pragmatist) had a number of questions about this:

I worked at a location that was running a single, world-wide instance of SAP. The whole of their HR, Finance, and some of their manufacturing was running from this single instance, twenty four hours per day, seven days per week.

Naturally, the process analyst in me (and to some extent, the pragmatist) had a number of questions about this:- “How do you back-up?” - “We mirror and back-up the mirror”

- “How do you do maintenance?” - “We have a back-up machine at a separate location across town. We transfer the users to that and perform the maintenance then”

The questions went on and on. Each one had a suitable reply. But then I started thinking about this single instance and it didn’t seem to sit right with me. For some reason I could foresee problems with it. Finally, I was able to verbalise the issues I was having: “How do you deal with disaster recovery?”

Most of my readers will know what disaster recovery is, but for those that do not, a quick explanation. When something happens to a computer system that renders it unusable, a business continuity plan (BCP) needs to kick in. This is where processes are enacted that allow the business to continue operating without the damaged/unusable machine. Running in parallel with this is a recovery process that attempts to repair or replace the damaged/unusable machine and reinstate all the data and transactions that were damaged or missing as a result of the disaster. I had concerns that because this was a single instance, and because it was being used globally, BCP and disaster recovery would be a nightmare.

The project team had already thought about this.

They told me that for BCP purposes, every affiliate running the software had processes on-site that would kick in if the system was unavailable. Even in the worst case scenario, the system would not be offline for any more than 48 hours because they had an agreement with a third-party provider to have a hot-site at a remote location which would be implemented at the first signs the redundant back-up didn’t work.

I asked if this had been tested. It hadn’t. But I was assured that it had been implemented in other organisations within 48 hours.

I turned my attention to the redundant back-up. What happens if there is a fire that destroys the main machine? The redundant back-up would kick in, and all systems would be re-routed. How is the rerouting done? Through underground cables that link the two sites. What happens if someone cuts through the underground cables? There are redundant underground cables that route North and South of the city between the two sites. The chances of both being cut are infinitesimally small. What happens if there is a power spike that takes out both systems? Both systems run off separate power supplies. A power spike would only take out one, not both. What happens if a small nuclear device takes out the town, both sites and the power sources? We would have bigger things to worry about than the system, but in that case the hot-site would kick into action.

I grilled the technical operators and designers of this system for almost two days, coming back to them time and time again when a new scenario occurred to me. They had a suitable answer for every single one of my questions. So, at the end of it - despite my reservations - I had nothing concrete to justify them

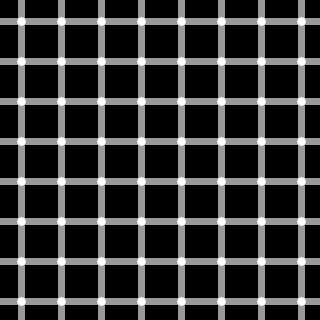

Then, a couple of weeks after I left the site they ran a new interface program. It was an HR population interface that filled in specific records on an HR master file. The interface had not been tested properly and it went into a loop. The program ran all day and most of the night. It kept populating the file overnight, making this file larger and larger and larger. It made it so large, in fact, that it completely filled all the disk space on the system.

The main computer, and global SAP instance, shut down.

As designed, it failed over to the redundant back-up across town. The system was on-line, ready to go as expected. It dutifully continued running all the processes it should be running - including the HR population interface. This ran for the rest of the night until it, too, had filled up the disk space on the redundant back-up.

That machine failed.

Plan C was, of course, the hot-site located in another town. A town which was, in fact almost 500 miles away from where the two main sites had been. The hot site didn’t work. It took almost 72 hours to get up and on-line and even then all the information needed to make the system run globally wasn’t there. The comms lines to the global sites were not connected. Anything that could go wrong, did go wrong.

The rest of the story gets a little fuzzy. All I know is that the global SAP system did not come back on line in the host town for almost six weeks. Retrofitting all the missed transactions from within the BCP took another few months.

Nobody lost their job over this. The hot-site provider lost their contract, I believe. I sat there shaking my head.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. The worst part came when I spoke to people who were affected by the outage. I asked them what their BCP was for when they had no access to the system. (remember I had been told by the tech crew that each affiliate had processes for dealing with on-going business when the system was down). They told me “We wait.” The BCP for operating a multi-billion dollar global business across numerous affiliates, sites and countries was “Wait”. Wait until the redundant back-up kicks in and, if this doesn’t work, wait 48 hours until the hot-site is ready to run. I wondered how they dealt with a six week backlog of waiting? Nobody was able to tell me. But I’m reasonably sure it involved manual work arounds.

The moral of the story?

Your redundant back-up isn’t. There is always the scenario where you will find yourself without it. Plan for that scenario. Make sure that you have processes in place to deal with it - even if the chances of that happening are remote. Remember the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre were designed to withstand the impact of commercial airliners when they were built. The chances of an airliner destroying more than a few floors was negligible. But the impact of the jets didn’t bring down the towers. It was the thousands of gallons of jet fuel burning away at vital support beams that did it. Once a couple of these had weakened, gravity did the rest.

Photo Credit: pchow98 via Compfight cc

Reminder: 'The Perfect Process Project Second Edition' is now available. Don't miss the chance to get this valuable insight into how to make business processes work for you. Click this link and follow the instructions to get this book.

All information is Copyright (C) G Comerford

See related info below

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ec1ab922-f985-472b-ad5d-4cdfa4aa10be)